Audio deep fakes threaten elections

Eleanor Sa-Carneiro

Front of mind

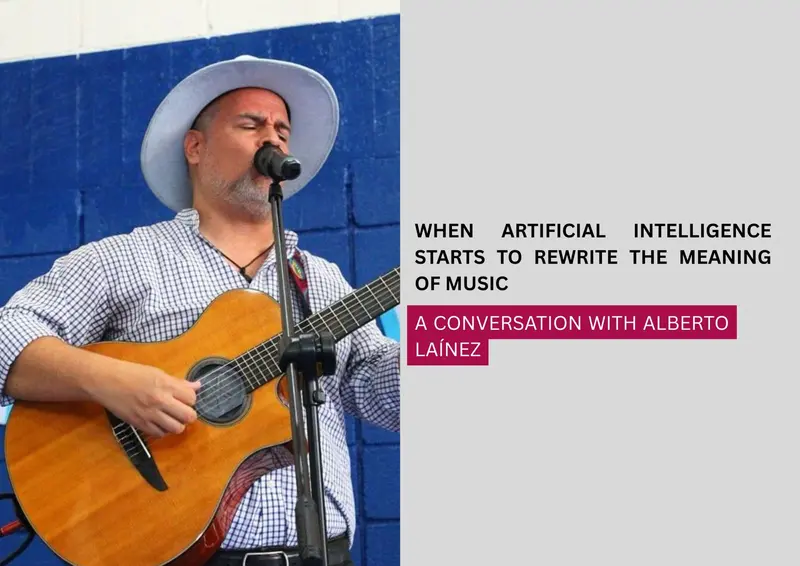

Authenticity vs AI: Alberto Laínez on the future of music

Amid the rise of AI-generated music, Honduran artist Alberto Laínez, known as El Aullador, reflects on the struggle to preserve human emotion, culture, and identity in the age of algorithms.

In a time when AI is rapidly generating music at scale, the Honduran singer-songwriter Alberto Laínez, better known by his artistic project name El Aullador, finds himself wrestling with a paradox. He embraces technology as a tool, yet fears it may eclipse the emotional core of his art, even usurping the very voice he pours his heart into. Laínez grew up singing in Honduras, and El Aullador blends his work as an environmental engineer with his love for music. He composes songs inspired by forests, wetlands, and protected areas, often working side by side with local communities. He asserts that his musical mission is ecological, to awaken in listeners a deeper respect for nature. His creed is simple: the songs do not belong solely to him but to the people who live the stories behind them.

READ MORE Continue reading Authenticity vs AI: Alberto Laínez on the future of music

From West Africa to Latin America: Why the Global South is ground zero for Bots-as-a-Service

With banks, governments and small businesses under fire, Bots-as-a-Service is exposing the Global South’s digital vulnerabilities.

Cybercrime is no longer the domain of elite hackers working behind closed doors. Today, it has become an open marketplace where criminals can simply rent the tools they need. Known as Bots-as-a-Service (BaaS), this trend is hitting the Global South hardest, turning countries in Africa and Latin America into both prime targets and unwilling enablers of global cybercrime.

READ MORE Continue reading From West Africa to Latin America: Why the Global South is ground zero for Bots-as-a-Service